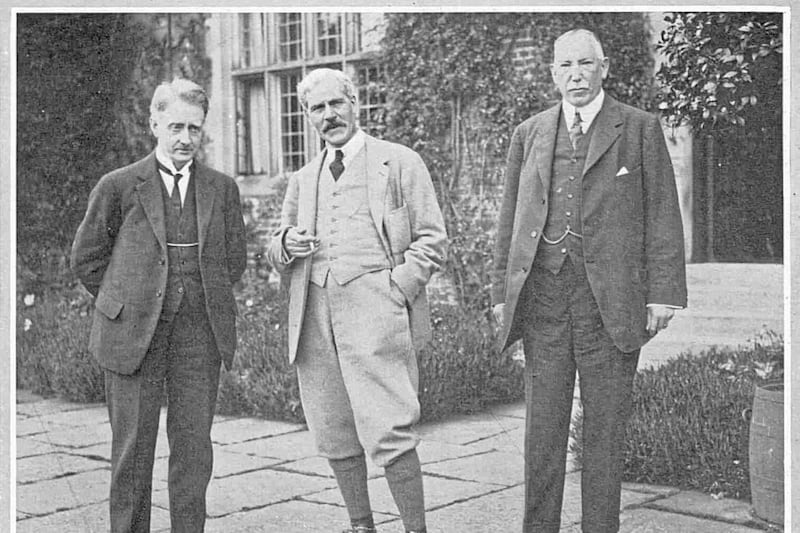

ONE hundred years ago, on July 20 1923, the president of the Irish Free State executive council, WT Cosgrave, announced in Dáil Éireann that he had appointed Eoin MacNeill as the "best person to represent the Saorstát [Free State] as our Nominee on the Boundary Commission".

"Dr Eoin MacNeill, I am happy to say, with great public spirit and self-sacrifice, consented to act in this most responsible and arduous capacity," said Cosgrave.

Two-and-a-half years later, after the findings of the Boundary Commission were revealed to both the Irish Free State and British governments in late 1925, Cosgrave's assessment of MacNeill's performance as commissioner was markedly different, describing it as "deplorable":

"He was a philosopher and had been out of touch with the feeling on the border."

Knowing MacNeill's character, why then did Cosgrave appoint him in the first place and how much blame should be apportioned to MacNeill for the disastrous outcome of the Boundary Commission that followed for nationalists, particularly northern nationalists living close to the border?

Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, a Boundary Commission would determine the border once Northern Ireland opted out of the Irish Free State in December 1922, consisting of three members: one appointed by the Free State government, one by the Northern Ireland government and the chairperson appointed by the British government.

Read more:

Partition: How the civil war solidified Northern Ireland’s status

Will Britain move the goalposts for border poll on Irish unity?

With hostilities of the civil war, by and large, over by the summer of 1923, the Free State government was in a position to deal with the Boundary Commission, the main outstanding issue emanating from the Treaty.

Cosgrave wanted to choose a minister in his cabinet who was also a northerner and a Catholic. While two ministers were from the north, Ernest Blythe and Eoin MacNeill – both born in Antrim – Blythe was a Protestant and MacNeill was a Catholic.

At the time, MacNeill was Minister for Education. Why Cosgrave believed it was necessary to choose a cabinet minister is unclear as there were only seven members at the time, all extremely busy with their own departments.

Almost a year later, in June 1924, the British government appointed the chairperson, Richard Feetham, a British-born judge based in South Africa. With the northern government refusing to appoint its commissioner, the British intervened by selecting Joseph R Fisher, a barrister and former editor of the Belfast unionist-leaning newspaper the Northern Whig.

While both Feetham and Fisher were from legal backgrounds and were devoted full-time to the Boundary Commission for its duration, MacNeill had no legal experience and retained his position as Free State Minister of Education, meaning he could only deal with the Boundary Commission on a part-time basis.

Cosgrave should have appointed someone outside the cabinet and from a legal background, someone like Kevin O'Shiel. O'Shiel was a barrister and land commissioner from Co Tyrone who served as assistant legal adviser to the Free State government, as well as – crucially – being director of the Free State government's North-Eastern Boundary Bureau, established in October 1922 to compile data and promote the Free State case for the Boundary Commission.

Instead, MacNeill was chosen, and although he was a politician, he showed a remarkably poor political grasp of matters while serving as the Free State Commissioner. Firstly, MacNeill decided to take a quasi-judicial view of his functions and adopted a detached almost-neutral viewpoint to proceedings instead of advancing the nationalist cause, as was expected of him by the Free State government, northern nationalists and indeed the British and Northern Ireland governments.

He also stuck rigidly to the Commission's decision to treat its proceedings as confidential at its first meeting in November 1924, unlike Fisher, who was in constant communication with the wife of Ulster Unionist MP David Reid, providing updates on the Boundary Commission proceedings which were then filtered through the Ulster unionist ranks.

While James Craig and his colleagues were fully aware of all the happenings of the Commission from late 1924 to late 1925, Cosgrave and his colleagues were kept in the dark by MacNeill, only becoming aware of the Commission's finding in November 1925 with the leak of the 'forecast' revealed in the Morning Post newspaper.

Historian JJ Lee's assessment of MacNeill as "an honourable and guileless man, who seems to have combined integrity with incompetence", seems apt for his performance as Boundary Commissioner.

While MacNeill certainly cannot be blamed for the vague and ambiguous terms of the Boundary Commission as agreed in the Article 12 clause of the Treaty, he can be blamed for not insisting on an agreement at the outset amongst the three Commissioners of the interpretation of Article 12, once the Commission convened.

Showing far too much deference to Feetham, while MacNeill may not have acquiesced to Feetham's interpretations of Article 12, there is little evidence of him opposing them with any vigour, if at all. Given that all of Feetham's interpretations and decisions favoured the unionist over the nationalist case, for which he became known in nationalist circles as 'Feetham-Cheat'em', this was a shocking dereliction of MacNeill's duty as Free State commissioner and as the de-facto representative for northern nationalists.

Feetham decided not to conduct a plebiscite, choosing instead to assume a quasi-judicial approach and ruling out wholesale transfers, disadvantageous to nationalists. Feetham looked at economic conditions as they prevailed in 1924/25 and not how they were interpreted by the Treaty signatories in 1921, again disadvantageous to nationalists. In fact, Feetham refused to hear any evidence on how the Treaty signatories interpreted Article 12, despite its obvious ambiguities.

This proved highly damaging for the nationalist cause. Feetham decided that smaller units such as district electoral divisions, instead of large units such as entire counties, should form the basis of areas to be considered for transfer, also disadvantageous to nationalists. He also gave primacy of economic and geographic conditions over the will of the people, the primacy of the Government of Ireland Act 1920 over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and that the Irish Free State could lose as well as gain territory, all decisions disadvantageous to nationalists.

While all of Feetham's rulings were a devastating blow to the nationalist and Free State cause, MacNeill remained silent, for the most part. From looking at the Boundary Commission files, downloadable for free through the UK National Archives website, throughout all the meetings amongst themselves and with the hundreds of witnesses they met, Feetham dominated proceedings, with minimal input from MacNeill, and indeed Fisher.

According to Paul Murray, when MacNeill did intervene, he was "neither probing nor forceful, giving the impression that he was a disinterested, aloof spectator".

Unsurprisingly, it resulted in the Boundary Commission recommending by mid-October 1925 minimal transfers to the Free State but also transfers from the Free State to Northern Ireland.

What is surprising is that MacNeill accepted the new boundary line as drafted then and did not dissent when this was confirmed in early November.

He only dissented after resigning from the Commission as well as the Free State government in late November, following the furore over the largely accurate 'forecast' of the Boundary Commission award by the Morning Post on November 7.

By signing an agreement and not resigning once it was clear the Boundary Commission's findings were totally at odds with Free State expectations nor by writing a minority report outlining his opposition, Feetham and Fisher naturally assumed there was unanimous support for the Commission's award and were both taken aback by MacNeill's resignation and subsequent opposition to their award.

In his resignation speech to the Dáil on November 24, MacNeill conceded "that a better politician and a better diplomatist, if you like, a better strategist, than I am would not have allowed himself to be brought into that position of difficulty".

He weakly defended his decision to initially support the Boundary Commission's award as the "ground for that agreement was purely and simply this: that the form of the award, when it appeared, should provide the least possible fuel for renewed, perhaps embittered, controversy".

Even though he fundamentally disagreed with the award and how Article 12 was interpreted, he bizarrely felt it was preferable to have the award signed by all three commissioners to avoid courting controversy, instead of publicly opposing an award that was undoubtedly humiliating for the Free State, an award that Cosgrave rushed to have shelved and hidden from the public at the earliest possible opportunity.

While MacNeill was undoubtedly offered a poisoned chalice when appointed as the Free State government's representative on the Boundary Commission in July 1923, given the vague terms of Article 12 and his minority position within the Commission, it is doubtful that anyone else could have wrought a solution satisfactory to nationalists.

However, MacNeill could have made a stand on how Article 12 was being interpreted by Feetham. Politically, he should have kept his Free State government colleagues abreast of developments. He should have promoted the nationalist cause instead of being a neutral observer.

His detachment and lack of engagement throughout the Commission's proceedings was unacceptable and his agreement to sign an award that was totally at odds with nationalist expectations was particularly indefensible.

MacNeill's blunders and what appears to be a total lack of awareness of the impact the Boundary Commission decisions would have on northern nationalists turned what could have been an awkward and embarrassing episode for the British government into one for the Free State government leaders, Cosgrave and Kevin O'Higgins, instead – who, partly to save face from the position MacNeill had put them in, sought for the Boundary Commission report to be shelved and for the border to remain as it was, as it is today.

:: Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).