Leadership figures in the republican movement involved in the development of the peace process were a “protected species” a prominent peace campaigner has claimed.

The suggestion has been made by Derry native Denis Bradley, who has penned a new book about his life and part in forging a peace deal to end the Troubles.

‘Peace Comes Dropping Slow: My Life in the Troubles’ sheds fresh light on a backchannel between the Provisional IRA and the British in the years before and during the peace process.

A former priest, who gave the last rites to some of those killed by British soldiers on Bloody Sunday, Mr Bradley later became involved in the backchannel with several others, including fellow Derry men Brendan Duddy and Noel Gallagher.

The backchannel provided a secret link between the IRA and the British government for three decades.

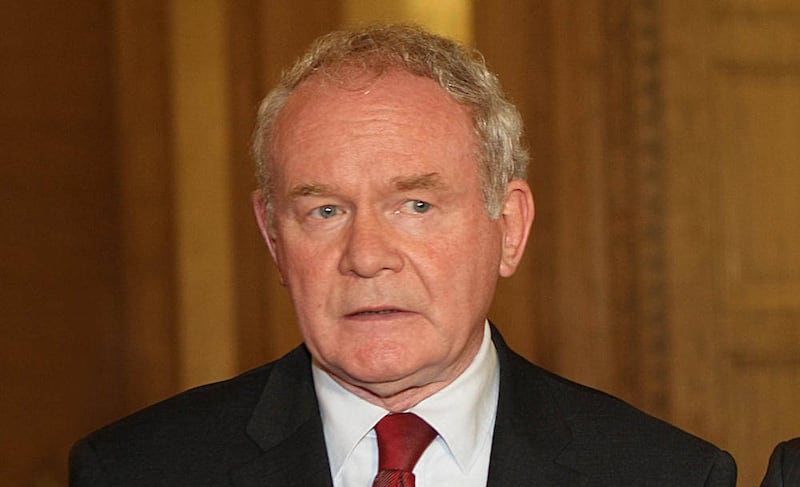

Mr Bradley and his backchannel colleagues are credited with setting up a meeting between between former Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness and North Belfast assembly member Gerry Kelly in 1993, both of who he says were IRA ‘Army Council’ members at the time, and MI5 man Robert McLarnon, who was known by the codename ‘Fred’.

The crunch meeting is viewed by some as a vital step on the road to negotiations that led to the IRA ceasefires and ultimately resulted in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

There has been some speculation about the exact role played by Mr McGuinness, who died in 2017, within the republican movement with some even suggesting he may have been compromised.

But speaking to The Irish News, Mr Bradley, who had close dealings with Mr McGuinness over many years, and who officiated at his wedding while still a priest, said he never had any indication that this was the case.

“There’s a great ability within the post conflict situation to speculate - speculation is a long way from any kind of solid reality.

“I have no indication whatever, knowing McGuinness for the length of time I knew him, that anything like that could be true.”

However, the former Policing Board vice chair, does believe that senior members of the republican movement were given special status.

“Not alone was McGuinness a protected species. McGuinness, Adams and that whole leadership was a protected species and that was partially down to the backchannel who were thumping at the British government that these were the people who were going to bring peace,” he said.

“I left the backchannel for about six or seven years and went back because of a conversation with McGuinness, where he talked about the need for Sinn Féin to become peacemakers.

“And I went back into the backchannel for that reason, because he and Brendan Duddy didn’t particularly see eye to (eye), well, they weren’t particularly first cousins in that sense.

“Personality wise, there was a bit of a clash there.

“So, I went back into the backchannel….because specifically I believed McGuinness could actually deliver what he wanted to achieve.”

Mr Bradley believed at the time that Mr McGuinness “was incredibly influential” and he and others in the back channel were telling the British that “this group of leadership within Sinn Féin (and the) IRA would deliver peace and were capable of it”.

“And that they had to, not protect them, but they had to make sure that they stopped this nonsense about we were going to defeat them militarily because the IRA were far from being defeated militarily,” he said.

In years before the Troubles ended hundreds of people were killed and imprisoned, including many members of the republican movement.

Asked if he believed that some republicans were kept alive, protected from arrest, or shielded from being deposed from within their own movement, Mr Bradley appeared to suggest a path to peace was in place.

“I’m not in a position, and it certainly doesn’t claim in the book, that any of that happened but you can read between the lines that actually there was an effort from very early on in 1990 to actually begin the process,” he said.

“And it stumbled along and it stumbled here and it stumbled there but….the road was in some ways laid out that we had to go down and the question was would we go down?”

He added that former British Prime Minister John Major “found it difficult” but that ex-Taoiseach Albert Reynolds “who got the situation fairly fast”.

Mr Bradley believes Mr McGuinness was eventually drawn to the idea of peace for a variety of reasons.

“I think if I was pushed I would say that McGuinness had both a change of heart but also a change of strategy at one in the same time,” he said

“I think that he was around long enough to realise the ineffectiveness of violence to bring about the real change that he would have wanted.”

Published by Merrion Press ‘Peace Comes Dropping Slow: My Life in the Troubles’ is available now.